TypeScript and the developer self control problem

In the paper “An economic theory of self control” nobel prize of economics Richard Thaler attempted to explain why sometimes individuals would impose constraints in their future behavior, like retirement plans, diets or smoke quitting treatments. He came up with a “two-self” model, which basically said every individual has a self-planner and a self-doer. Some individual decisions are the result of the interaction between the planner and the doer. The planner knows what is best in the long term, but it has to deal with the doer, which only thinks about what is best in the very short term. To avoid the doer deviating from the long term plan the planner limits the set of choices the doer has available at any given time.

As a former economist, when I first read about Typescript the planner-doer model was one of the first things that came up to my mind. We can think about Typescript as a set of tools the planner-coder can use to limit what the doer-coder can do.

Typescript and the constraints to the doer-coder

As we said, we can see Typescript as a way to define constraints to the doer-coder in order to make a better code. To make this possible Typescript makes available to us something called “types”. With “types” we can limit basically two things:

- the types of parameters a function or a variable can get

- and the values a function can return

This is why we say Typescript is statically typed as opposed to javascript, which is dynamically typed. The first one implies types are checked at compile time, while the second implies types are checked at runtime. With Javascript we will run into type errors at runtime, but with typescript at compile time, which probably is safer. In other words, to find type errors in javascript we need to execute the program and with typescript we dont. This makes a better developer experience and easier to catch bugs.

Defining constraints

Types are the language we use to write the constraints for the doer-coder. Typescript gives us a set of core types, but also allows us to use other tools in order to be able to write these rules in the most precise way possible. The most important core types are:

- String

- Number

- Boolean

- Object

- Array

- any

One important thing to mention is that when we use the type “any” we are telling TypeScript the value can have any type. Basically, the result of using any is that types are going to be checked at runtime only, like in javascript.

The following example is the same as saying “function A must receive only two arguments, input1 and input2, and the first one needs to be a string and the second one two. Moreover, the result must be a number”

function add(input1: number, input2: number): number {

return input1 + input2

}Get proficient writing constraints

As we said, Typescript gives us a broad range of tools to write constraints. Lets see the most important with examples:

Literal types

Literal types useful when we want to specify a value can only take a set of exact values. For example, resultConversion can only take the exact values of “as-number” or “as-text” | "as-number"

function addNumbers(input1: number, input2: number, resultConvertion: 'as-text' | 'as-number') {

if (resultConvertion === 'as-number') {

return input1 + input2

}

if (resultConvertion === 'as-text') {

return (input1 + input2).toString()

}

}Type aliases and interfaces

TypeScript gives us ways of adding layers of abstraction to the typing of functions and variables. With them we can better resemble in the code the relations between the different real world entities we are working on. Lets take, for example, the PostPage component of this blog.

This post page receives as props an object of type Post, which is defined this way:

import React from 'react'

import { PostType } from 'src/types/post'

import PageWithLayoutType from 'src/types/pageWithLayout'

import { getPostBySlug, getAllPosts } from 'src/lib/posts'

import PostBody from 'src/domain/post/postBody'

import Layout from 'src/components/layout/postlayout'

type PostPageProps = {

post: PostType

}

const PostPage: React.FC<PostPageProps> = ({ post }) => {

return (

<>

<PostBody source={post.content} />

</>

)

}As we can see a Post object is an object with a set of fixed attributes, each with a specific type. For example, each Post object must have an “title” attribute with a value of type string:

import Author from './author'

type PostType = {

slug: string

title: string

date: string

coverImage: string

author: Author

excerpt: string

ogImage: {

url: string

}

content: string

}

export default PostTypeThe difference between type aliases and interfaces is the latter are extendable and that is why TypeScript recommends to use them instead of type aliases.

Union types

Sometimes we have a function which we know one or more of its parameters can be of different types. Lets take the MediaSlider component example mentioned in this blog post MediaSlider is a component which can get as props a group of videos slides or a group of photos slides and we want it to display them differently:

type MediaSliderProps = {

slides: Photo[] | Video[];

};

export const MediaSlider: React.FC = ({ slides }: MediaSliderProps) => {

if (!slides) {

return null;

}

if (isPhotoArray(slides)) {

return (

/* photo array stuff here */

)

}

return /* video array stuff here */

}Intersection types

On the other side, ocassionally we need to combine types. Lets take a look at how the persistent layout is handled in the blog (you can check more on this post or in the github repository ). PageWithMainLayout is a NextPage component (a special component Nextjs uses to render pages) with a layout property of type MainLayout, which is a one of the layouts which are used in this blog. To make the combination possible we use the “&” operator:

import { NextPage } from 'next'

import LayoutMain from 'src/components/layout/mainLayout'

type PageWithMainLayout = NextPage & { layout: typeof LayoutMain }Type guards

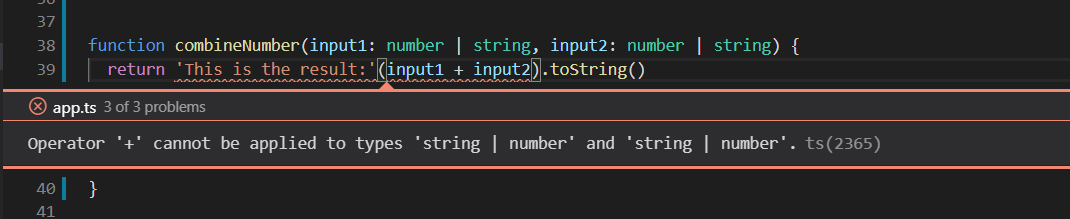

In the case we are using union types (type example: string | number) Typescript will ask us to take some precautions, which are called “type guards”. The problem we might have a runtime when using union types is this one:

To avoid we have several types of type guards at our disposal:

- type predicates

- in operator

- typeof

- instanceof

- adding new property to be able to differentiate

I will get on each one of these methods in deep in a future post, I promise.

Typing a function as a parameter

Frequently we will found our selves passing a function as a parameter. Likely for us, TypeScript allows to constrain the shape the function can take. For example, the function calculation() receives two parameters and returns a number.

function printResult(

input1: number,

input2: number,

calculation: (inputA: number, inputB: number) => number

) {

console.log('This is the result', calculation(input1, input2))

}Function overload

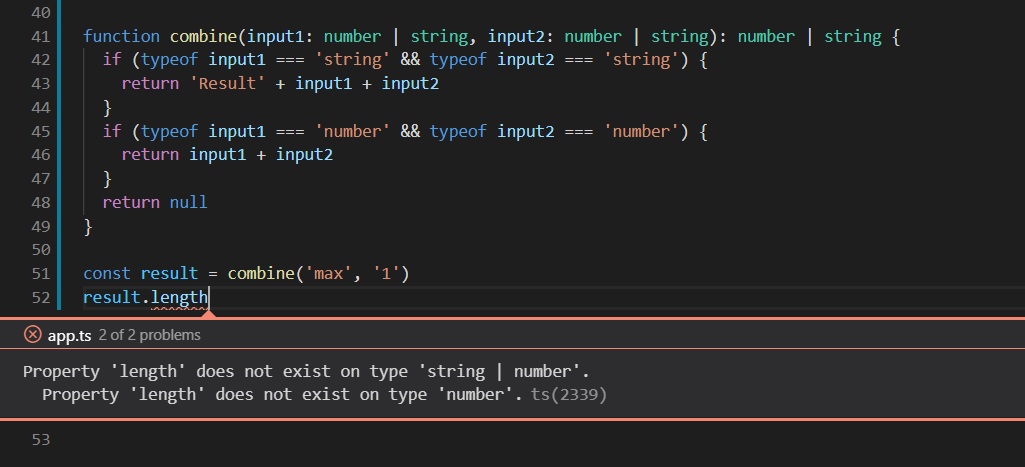

Is not uncommon in Javascript to see functions which return different types of results depending on the type of parameters they get. In the following example we have a function which receives two parameters which can be of type number or string. Also, the output of the function can be of result number or string.

But when we try to apply string methods to it like length, it warns you that something is wrong. The issue of using types this way is TypeScript don't know exactly which type the result is.

The solution is to use “overloads”. What we do with them is better specify the nature of the constraint.

function combine(input1: string, input2: string): string

function combine(input1: number, input2: number): number

function combine(input1: number | string, input2: number | string): number | string {

if (typeof input1 === 'string' && typeof input2 === 'string') {

return 'Result' + input1 + input2

}

if (typeof input1 === 'number' && typeof input2 === 'number') {

return input1 + input2

}

return null

}

const result = combine('max', '1')

result.lengthHere what we did was to tell TypeScript if the function receives tow parameters of type string, then the result must be a string. If both parameters are of type number, then the output must be a number. That way we can apply to the result contant string or number methods without getting any warnings.

There are still some topics to cover about typescript like generics, type guards and how to use TypeScript with React, but I will get to them in a later post. Stay tuned!